Arianism

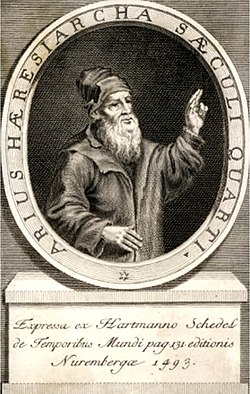

Arianism is a heretical nontrinitarian doctrine developed by the heresiarch Arius, a presbyter in Alexandria who lived between c. 256 CE and 336 CE. Arius argued that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is not co-eternal or consubstantial (of the same essence) with God the Father. Instead, Arius taught that the Son was a created being, brought into existence by the Father, and therefore subordinate to Him.

The controversy surrounding Arianism dominated the 4th century and was a primary focus of the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. The council condemned Arianism and affirmed the doctrine of the Trinity, declaring that the Son is "begotten, not made, being of one substance (homoousios) with the Father." Despite this, Arianism persisted for centuries, especially among certain Germanic tribes, before gradually declining.

This doctrine's emphasis on the created nature of the Son directly contradicts orthodox Trinitarian theology, which asserts the equality and unity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Arianism was entirely extinct between the 7th - 19th century, until being revived by the heretical restorationist denomination called the "Jehovah's Witnesses".

Arianism's influence extended beyond theological debate to political and social spheres, particularly during the reign of Emperor Constantius II, who supported Arian sympathizers. This alignment politicized the controversy, dividing the early church into factions and sowing discord within the Roman Empire. The theological dispute became a defining feature of the struggle for Christian orthodoxy, with councils convened repeatedly to address the issue. Although the Nicene Creed initially resolved the matter in favour of Trinitarianism, subsequent compromises such as the Semi-Arian stance, which proposed that the Son was "of similar substance" (homoiousios) to the Father, prolonged the conflict. These divisions underscored the early church's challenges in defining and preserving doctrinal unity amidst competing interpretations of Scripture.